Note: Because this post talks about pregnant female bodies and uses diagrams to point out particular conditions, be advised that there are drawings that showcase naked bodies below. This post may not be deemed safe for work.

Pregnancy is rough. It changes your body in preparation for a major event to take place. A baby will be born—when it comes to the things a female body can do, that’s one of the most remarkable.

When it comes to the aftermath, however, it can be kind of confusing. Hips spread. Boobs increase. Belly…wait, what is going on with the belly?

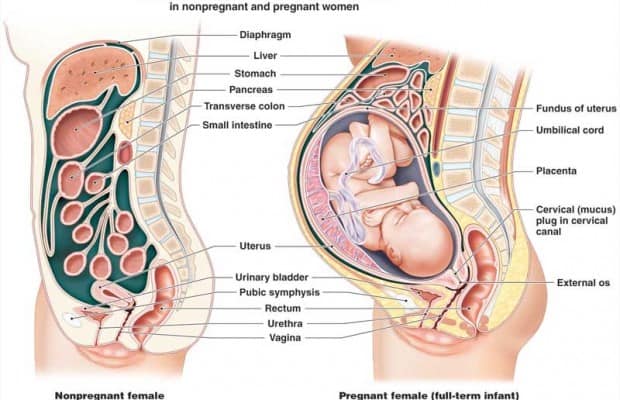

As we’ve talked about before, when the fetus grows inside the uterus, it grows upward towards the rib cage and outward away from the spine, but it does so behind your abs (we call that ‘the abdominal wall’) which is designed to help you push when it comes time to deliver.

Though it isn’t marked in the diagram above, the abdominal wall lies between the uterus and the outer skin of the belly area. It provides cover from outer forces, but it’s also susceptible to its own kind of damage.

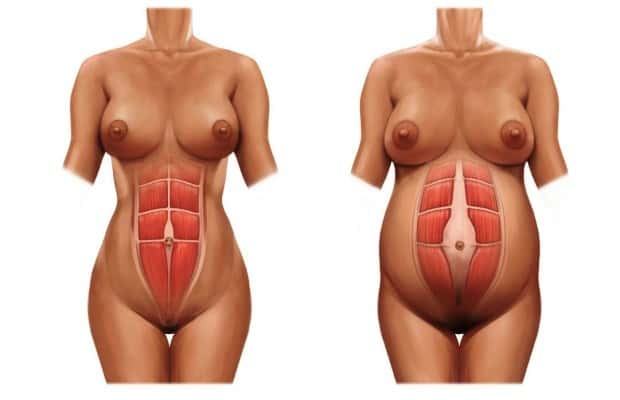

As the uterus grows and expands to accommodate the fetus, the abdominal wall must stretch, as well. The muscles themselves don’t give way, but the connective tissue that connects muscle to other muscle—known as fascia (pronounces fa-shuh)—does, specifically the line of connective tissue right down the middle of the stomach known as the “linea alba,” which is basically Latin for “white line.” It’s literally “the white line expanding down the center of your stomach.” This condition, the spreading of the linea alba, is referred to as “diastasis recti”—the separation of the abdominal muscles.

In lots of cases, abdominal separation can be predicted: giving birth to multiples, giving birth to a single large baby, or giving birth in your late 30s or beyond are often signs that you may have a challenge with diastasis. As you age, the health of your connective tissues—not just tissue that connects muscle to muscle, but muscle to bone and bone to bone (tissue connecting bone to bone is also known as “joints”)—tends to deteriorate without proper care as you age, which leaves you more susceptible to healing improperly or not healing from it at all. A quick google images search will show images of people who either healed improperly or developed hernias, which are when the intestines or other vital internal organs push through the abdominal wall.

And, when it comes to multiples or particularly large babies (with large being defined in relation to the size of the person carrying it), it’s fairly obvious: the larger the load, the more pressure on the abdomen, the more expansion required of the abdominal wall to make room for it. It’s a situation ripe for diastasis.

Does it matter if you’ve given birth vaginally or via cesarean? No, although it can make a difference in how you heal. Because c-sections require that connective tissue be cut, the abdominal wall is sometimes stitched back together so there’s little worry, but not all doctors do this the same way. Many doctors now cut at the “bikini line” instead of cutting from breast to pubic bone (or “from north to south”), but it’s something worth discussing with your doctor to be sure you know. Giving birth vaginally isn’t protective from issues, since the weight of the infant is the determinant, not how you deliver.

How do you know if diastasis is what’s causing your tummy pooch? Check out this video.

If, while doing this little test, you happen to notice something protruding from the space between your abdominal muscles, consult your OBGYN immediately.

Suppose you’ve determined you have diastasis recti. What can you do about it? Honestly, a lot.

The first thing you can do is take it easy. Post-delivery, spend lots of time laying back and relaxing as much as you can. Not only does your body need to get used to no longer being pregnant, but you need to get used to moving around without a giant mass in your stomach weighing you down and pulling you forward, and that takes time. Because the abdomen has shifted in such a drastic way, your lower-torso will be much weaker. Do as much standing and sitting as you can, but do it assisted—hold on to a rail, a bench, a desk, the arm of a chair, anything—until you’re sure you an go without.

Speaking of a weakened core, consider wearing your baby. Most methods of baby wearing require a long piece of fabric to be wrapped around your core and back, while strapping the infant to your chest. Lots of people invest in expensive fabrics by brands that cost hundreds of dollars, but I bought a 18′ piece of jersey knit fabric from a local fabric store for less than $15, and was more than set. Some prefer a sturdier fabric with less stretch to it, because the jersey knit has enough pull to it that the baby starts to feel like he or she is sliding down, but the sturdier fabrics actually gave me lots of back pain. The photo you see of me here on my blog sidebar—also posted below— is me wearing Baby Sprout.

Baby wearing provides tons of comfort for you and baby, sure, but it also helps hold the abdomen together, preventing the weight of sagging abs from further pulling the connective tissue apart. You don’t have to wear baby all day, but a couple hours a day—maybe while going for a light walk?—can make a world of difference not only for baby’s temperament and your sanity—your little one will love being so close to your heartbeat, your smell, and your warmth, and will be soothed by it!—but also for your abdomen.

A third thing you can do is add a few particular things to your daily diet. Connective tissue is largely made of collagen, found in many places throughout the body. Consuming collagen combined with the nutrients that best support its health and growth are ideal. Bone broths are all the rage now, being touted for the ability to impart marrow, collagen, and any other number of benefits to the body. The truth is, however, lots of cultures have been making soups using animal bone and joints to make the base, and then loading the soup itself up with dark and leafy greens, legumes like chickpeas, garlic, onion, and various herbs and spices. (I’m specifically thinking back to my mother’s collard greens with hamhock and onion, here. See, the elders knew what they were doing.) Eat the veggies, drink the broth, boom. All the amino acids necessary to build healthy connective tissue in not only your belly but everywhere are all inside your bowl and, eventually, your tummy. (also? Great for hair, skin, nails, and joint health.)

My fourth tip is what you shouldn’t do, and that’s ab-targeted exercises. Crunches, weighted upper-body moves like good mornings or stiff-legged deadlifts can potentially make the situation worse, and are best avoided. Stretches, like cobra pose or laying across an exercise ball, that elongate the abdomen are also grounds for concern. Honestly, anything that would require you to flex your abs is going to be a problem, because the lack of sturdy connective tissue weakens your core and leaves you at risk of injury. I mean, even coughing without supporting you tummy area is gonna make things rough.

There is such a thing as improperly-developed muscles. There’s also such a thing as muscles developed in an un-proportional manner. With abdominal separation, this is a high risk, and it’s far more difficult to undo. It’s worth just going easy for a while.

Speaking of things you shouldn’t do, let’s add “waist trainers” and “corsets” to the list. Both are far too restrictive and can prevent you from building the muscles that are most able to support your core. More importantly—at least, to me—they’re far too expensive for the purpose. That same baby wearing fabric I mentioned before? Just as helpful when you’re not wearing your baby. Wear a bit of it whenever you’re working out or being intentionally active, keeping in mind that this doesn’t give you back full functionality in your core, and it doesn’t necessarily repair your diastasis recti—it simply protects you from developing a hernia when you do.

Diastasis recti takes anywhere from six months to a year after delivery to repair, longer if you aren’t particularly active or tending to it consistently. It’s also worth noting that you may still have some belly fat to take care of after your separation has recovered. That’s particularly easy to tend to, though.

All in all, it feels like cause for panic, but it isn’t—it’s a natural part of the miraculous nature of childbirth. Keep your diet loaded with dark-and-leafies and healthy fats, take it easy, wear your new little one (or don’t if the little one is, say, 3 years old, now!), and keep off it for a while. It’s pretty simple! Stick to it—your tummy will thank you for it!

2 comments

Hello can u tell me excerises I can do to fix mine even doe my last is 8 years I will eventually get a surgery done but if there’s anything I can do…

There’s nothing I’d recommend that doesn’t have a considerable risk of worsening the condition or putting you at risk of injury. Just follow the advice in the post, and it’ll make a huge difference.

Comments are closed.