As I’ve said time and time again, even though I work in marketing… I really hate marketing. Don’t get me wrong – the right kind of marketing can be invaluable to both a business and the buying public. Others, however, only seek to obfuscate the truth and cover up something that might convince you to take your money elsewhere. That’s the kind of marketing I dislike.

And, so is the case with Aunt Jemima. As I was researching for the latest series for the blog, I happened to uncover this little beauty, retyped from The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink:

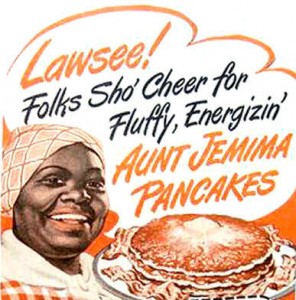

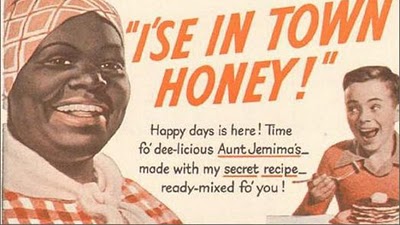

Aunt Jemima pancake flour, the first nationally distributed ready-mix food and one of the earliest products to be marketed through personal appearances and advertisements featuring its namesake, was created by combining advances in manufacturing and distribution with popular nostalgia for the antebellum south.

The product was originally named “Self-Rising Pancake Flour” and sold in bags. In the fall of 1889, Rutt was inspired to rename the mix after attending a minstrel show, during which a popular song titled “Old Aunt Jemima” was performed by men in blackface, one of whom was depicting a slave mammy of the plantation South. The song, which was written by the African-American singer, dancer and acrobat Billy Kersands in 1875, was a staple of the minstrel circuit and was based on a song sung by field slaves.

The pamphlet, as included in the text. The sentence reads as follows: "New ways in which millions of women are using it to make delicious pancakes, waffles and muffins"

Rutt and Underwood sold their milling company to a larger corporation owned by R.G. Davis of Chicago. He transformed the local product into a national one by distributing it through a network of suppliers and by creating a persona for Aunt Jemima. Davis hired Nancy Green, a former Kentucky slave and cook in a Chicago kitchen, to portray Aunt Jemima in that city’s 1893 Columbian Exposition. She served pancakes from a booth designed to look like a huge flour barrel and told stories of life as a cook on an Old South plantation. Her highly publicized appearance spurred thousands of orders for the product from distributors. Davis also commissioned a pamphlet detailing the “life” of Aunt Jemima. She was depicted as the actual house slave of one Colonel Higbee of Louisiana, whose plantation was known across the South for its fine dining –especially its pancake breakfasts.

The recipe for the pancakes was a secret known only to the slave woman. Sometime after the war, the pamphlet said, Aunt Jemima was remembered by a Confederate general who had once found himself stranded at her cabin. The general recalled her pancakes and put Aunt Jemima in contact with a “large northern milling company,” which paid her (in gold) to come north and supervise the construction of a factory to mass-produce her mix. This surprisingly durable fable formed the background for decades of future Aunt Jemima advertising.

The Advertising Campaign

The basic story was fleshed out and brilliantly illustrated through an advertising campaign in North American women’s magazines during the 1920s and 1930. The ads were the work of James Webb Young, a legendary account executive at the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency in Chicago, and N. C. Wyeth, the well-known painter and illustrator of such books as Treasure Island and The Last of the Mohicans. The full-page color advertisements ran regularly in Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping and the Saturday Evening Post and told tales of the leisure and splendor of the plantation South, complete with grand balls, huge dinners and visitors dropping in from across the region. Not too subtly, Aunt Jemima Pancake Mix, a labor-saving product, was marketed with comparisons to a time and place when some American white women had access to the ultimate labor-saving device: a slave. A line from a 1927 product display read, “Make them with Aunt Jemima Pancake Flour, and your family will ask where you got your wonderful southern cook.”

After aunt Jemima’s debut in 1893, her character was played by dozens of women in radio and, eventually, television commercials and in appearances at schools and country fairs. After Nancy Green, the original actress, dies in 1923, she was replaced as Aunt Jemima by Anna Robinson, a darker-complected and heavier (at 350lbs) woman. The image on the box and in ads was adjusted to resemble her more closely. Later, the actresses Aylene Lewis and Edith Wilson portrayed the mammy in some advertisements. Lewis also played the role at Aunt Jemima’s Pancake House in Disneyland, which opened in 1957.

However, the advertising icon, always a source of criticism in African American newspapers, came under increasing scrutiny in the 1950s and 1960s as first the civil rights movement and then the black power movement reached their respective crests. Local chapters of the NAACP began pressuring schools and fair organizers not to invite Aunt Jemima to appear. In 1967, Edith Wilson became the last woman to play Aunt Jemima in advertisements when the Quaker Oats company, which had owned the product since 1925, fired her and canceled its television campaign. Quaker Oats also took Aunt Jemima’s name off the Disneyland restaurant in 1970; Aylene Lewis was the last woman to portray Aunt Jemima on the company’s behalf.

Revising the Image

Throughout the 1960s, Quaker Oats lightened Aunt Jemima’s skin and made her look thinner in print images. In 1968, the company replaced her bandana with a headband, slimmed her down further and created a somewhat younger-looking image. She still appeared in print advertisements but without the heavy reliance on the southern plantation settings and largely without a speaking role. In 1989, Quaker Oats made the most dramatic alteration yet to Aunt Jemima’s appearance, removing her headband to reveal a head full of graying curls and adding earrings and a pearl necklace. The company said it was repositioning the brand icon as a “black working grandmother.”

In 1993, Quaker Oats debuted a series of television ads for the pancake mix featuring the singer Gladys Knight as a spokeswoman and using Aunt Jemima’s face only sparingly. The ads had a very short run, and Aunt Jemima continues to

hold a low profile in the advertising world, even though she consistently ranks as one of the most recognizable trade names in North America. Aunt Jemima pancake mix and syrup remain market leaders in the United States, and in the

1990s Quaker Oats even licensed the use of her name and image for a line of frozen breakfast products manufactured by another firm. Despite the controversy surrounding her image in the late 20th century, Aunt Jemima remains one of the most successful advertising icons of our time.

Now, compare that to AuntJemima.com’s “History” page. Sure looks whitewashed to me.

My overarching point, here, is that marketing can – and often is – used to manipulate the facts. It’s used as a tool to convince you to give me your money and not the other guy. And that’s fine – but as conscious consumers, we like to have all the facts. I can’t say that I’d support Aunt Jemima anyway because (a) I’m pretty sure that syrup isn’t much more than high fructose corn syrup and caramel color anymore, (b) my pancakes taste way better and (c) I’m not interested in paying triple the cost for a poor quality product. However, I couldn’t even tacitly support a company like this.

Just consider this a lesson in “epic whitewashing,” and a polite reminder that marketing is almost always hiding something.

38 comments

Wow, fascinating!

Far less egregious but not unrelated: Quaker Oats has nothing to do with Quakers, either. It’s a sales gimmick to imply plain, honest, down-to-earth quality. At least they didn’t–as far as I know–ever go so far as to invent a life and history for him, but he’s still Stereotyping Lite on a religious instead of racial basis.

Nevertheless, Quakers everywhere get asked all the time about oatmeal and why we don’t dress like the guy on the box.

Even better. Found THIS info, too. I’ll post later.

Uh, oh.

I have to confess: I didn’t care enough to look for it since we mostly laugh about it now.

I know a Kenyan whose last name is Enchemama, which apparently means “mother’s love”. Makes me wonder if there is a connection there.

Oh, WOW.

Wow. This is a lot of info to research to break down. Thanks for taking the time to do it!

Thank you sooooooo much for doing this bit of research! I would never have known the checkered past of the brand. Yes, I knew it had to be something, but to find ads and links to its slave mammy roots is all the confirmation we need. Makes me not want to buy them again for totally removing the true facts from the website! But then again, did we really expect them to tell the whole truth? I think not!!!

Not exactly sure if you are highlighting marketing tricks to dupe consumers into buying pancake mix and syrup or if you just wanted to demonstrate the history of Aunt Jemima’s syrup but the article came off as largely negative. As a black woman trying to be healthy, I can understand not wanting to endorse such a product but it is almost like you are hating on Aunt Jemima the image. There is a thin line between, being hated and self hating. We all have an aunt, mother, grandmother etc who looks like Aunt Jemima with her heas all wrapped up but does that make them slaves?? Did we not come from slavery? Yes generally Aunt Jemima is something none of us wanted to be growing up and most cartoon caricatures and food products like Uncle Ben have racist beginnings and if you don’t know your past you cannot understand your future but we must be careful not to demonize the concept of the black woman in the process like every other media outlet would. Because, although the image was racist and was not owned by a black woman – it employed a black woman who ultimately lost her job, with no equal paying job to replace it. In addition to that I ask you to compare this with Madame CJ Walker. This black woman became the first black millionaire due to a product that perpetuated self hatred yet most black people applaud her. Is there really a difference? Is it really okay that black women will perm the hair of a baby not even a year old, three years old or even 5? Is it okay that women who grow hair that is not straight only feel acceptable or beautiful if they have straight permed hair and expensive human hair from a strange country? This does not have to do with what a person consumes but has more to do with the perception or the image of black women in the eyes of others. Yes Aunt Jemima presented a negative image of a black womanhood but it also gave a black woman an opportunity to be elevated into stardom – negative or not. If we cannot present our own history in a fair objective manner how can we expect others to do any differently? We are the gatekeepers to our own history and we can re-write it objectively or we can continue the degenerative racial propaganda of others. We owe our ancestors better.

I’m not entirely sure of what I’m being accused, here, but I thought it was made pretty clear in the beginning that this is an excerpt from an encyclopedia.

How do I “demonize black women” by sharing the fact that a company built off the exploitation of a Black woman (and, apparently, a SERIES of Black women) tried to clean up its image by marketing, creating a false history for itself and STILL expecting you to give them your money?

I have a woman in my family who looks like Aunt Jemima – ME. And guess what? I don’t appreciate a company that’s over 150 years old still existing, selling processed garbage to MY people (those people who look like me and Aunt Jemima) and LYING about the past and how they manipulated who we were and who we are still to this day. “We cleaned up her image, gave her pearls and made her look like a working grandmother.” Word? Get out of here.

I’m not even sure what your comment is asking of me, but I don’t intend to stop sharing what I’m finding out about food and my culture in this country, mama. That’s all I can say about that.

Thank you so much for sharing this article and I agree with you 100%!!! What good is a black woman/en being propelled to stardom if it isn’t done in such a way to inspire others, particularly members of her own race? Lorrie discusses Madame C.J.Walker and hair relaxers, which was not even Walker’s contribution; however, Walker helped to promote women of color through beauty products aiming to maintain and manage their hair. On the other hand, Aunt Jemima products aimed to add even more convenience to white homes by the hands of black women. There’s a huge disparity here…

Thank you for writing this post. I’m so tired of seeing this character as if she is a blessing to Blacks. My pancakes taste so much better (as do my waffles that I make from scratch), and I don’t need some mammy mix to do it.

I feel like that’s another part of this that bothers me – the Pine-sol lady, the Popeye’s lady… what other women of color are there representing national brands, and in what capacity? I mean, it’s mildly disturbing.

Conversely, the Uncle Ben’s story is nowhere near as controversial – “Uncle Ben” really did exist, and really did harvest rice. His image was misappropriated by white farmers in the early 20th century, though, but (if I recall correctly) that’s about it. It’s just bothersome.

It always rubs me the wrong way when I see those ads. The only times you see black women in a professional capacity in advertising today are when they’re maids, fast-food workers, or other low-wage, low-prestige jobs. Meanwhile, black men are sometimes shown in ads set in offices–implying that it’s ok for white people, or black MEN, to have professional jobs, but not black women. It’s racist, sexist, and as a Southern white woman, it makes me wonder how anybody can have the gall to pretend racism is over. I saw it growing up in the 80’s and 90’s, I hear it on the news every day, and by Jove, I’ve heard dog-whistles long enough that I know when they’re being used.

I even remember as a little girl, having a plush doll–one of those kind that you flip the skirt up and it turns into a different person. Not a bad idea in and of itself, but one side of the doll was a blonde little girl, and the other side was a black “mammy” character! And my parents saw nothing wrong with buying me this racist doll! Once I realized the messages behind such a toy, I stopped liking that doll in a hurry. I see so much racism as someone who isn’t directly affected by it, it keeps me wondering what else is out there that I’m just not seeing because of my privilege.

As far as I’m concerned, all women are my sisters, and when so many are marginalized like this, the offenders are telling me that they don’t care about any of us women, black or white. (I believe the preferred phrase on the Internet is, “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit.”)

Thank you for being so thorough and helping some to understand that everything has a history. Cover up being something this country’s based on. You can’t believe everything that you’re spoonfed.

Erika,

Thank you for your post on this. Very interesting! I hear what you are saying. Yes, it is good to see our African American actresses and actors being employed in media – TV, printed ad, etc., but they are often associated with products and foods that are not healthy! Would love to see one of us featured in an ad that promotes health and wellness. Would love to see an ad with a sister cleaning her kitchen with Seventh Generation cleaner or a Whole Foods ad with a brother with his two kids shopping in their stores. We need to see those types of images – all the time. Not just in the health magazines but in mainstream ads, People Mag, Cosmopolitan, prime time on TV.

We need more of these positive healthy images.

Oh crap. I never made that connection before – fascinating. Not that I use Aunt Jemina stuff, but sometimes I hate learning about the history of companies because it starts cutting off things I can eat, or just leaving me a guilty mess. Pretty much every banana company I know of has a very evil, bloody history, but I love bananas so much… I’m guessing the bananas will stick around, but the history (and present) of soda companies is motivating me to stop drinking soda.

Thank you and I totally agree. We often are so unconscious or unconcerned about the influence of marketing, yet are among the most responsive.

Good article!

Speaking of Uncle Ben, they him CEO of the company a few years ago. Article: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/30/business/media/30adco.html?pagewanted=all

I remember looking at the website back then and being able to “tour” his office. I see they have downplayed it now.

WOW… good story it is exactly THIS reason i don’t buy this product .. people can try to “pretty” it up all they want but if you got a “mammy” on your pancake box I am not buying it….

Being a white woman myself, I have always wondered why this product continued to be purchased by anyone. I understand it came out it in a far more racist era, but really, selling Mammy Mix in the 21st century?

The other thing is, it is not very good. I had it at a friend’s place when I was in high school many years ago and I thought it made mediocre pancakes.

I’m sharing this one for sure. Very interesting. I think you’ve given me my theme for this year’s African American History Month…uncovering/debunking these negative images.

wow i did not know the true story. i just thought it was a knock off of a plantation stereotype and didn’t know they had worked really hard to sell it like that, with actresses etc. i think the syrup is mostly hcfc like most regular syrups are now. not sure if i’ve even had the pancake mix, might check the ingredients sometime.

LOL. Whitewashed is the perfect term.

I bought an old cast iron coin bank of Aunt Jemima. It’s adorable and I LOVE it. However, I don’t want to offend anyone. Do you think this is racist to have in my home?

I can’t speak for everyone else, because I think we all process things differently. Reactions to something like that could fall anywhere on the spectrum – some consider it memorabilia of a time where we were at our most hateful as a country and never want to forget what greed and laziness can do to us; others consider it people longing for the old days when genteel white ladies could sip their mint juleps on the porch and watch a slave breastfeed their children, wash their dishes and cook their dinners for them. That sounds dramatic, but it’s honest.

That being said, it’d definitely be a “conversation piece.” I’d want to ask you why you own it, and why you’ve chosen to keep it out and on display. I’d want to better understand the person I’m dealing with.

Truthfully, I think you should take a long, hard look at why you’re keeping it, and what keeping it out does to/for others. If people are joking and giggling at it, and it starts up racist conversations about the appearance of persons of color… then is it a good idea to keep it out and around? Only you can decide.

I so appreciate your thoughtful response, which makes me ponder why I love it. I can assure it is not racist. One of my initial thoughts is that she makes me think of the woman in the book, “The Secret Life of Bees.” The little runaway is scared and this woman envelopes her in her arms. It’s that place of safety. This woman loves her, not even knowing her. In “The Shack,” God is portrayed as a large black woman. It’s comforting. I guess when I look at this coin bank, I feel warm. I will have to explore any other reasons, besides the fact that her dress is red, and I DO love red! Thanks for providing an open forum here.

You wrote an incredible article that everyone should read. This Press Release links to your article as this the best explanation on as you say “marketing magic” (brilliant)

http://www.newswire.net/newsroom/pr/00077326-micheles-syrups-chicago.html

Michele Hoskins story is inspirational and she is the only African American syrup, really.

I ain’t even black, but this article opened my eyes! Being Mexican, I’m curious to see how America has white washed their involvement with my ancestors. I’m now curious about the marketing schemes behind Tapatio and Cholula hot sauces! Funny how googling things can start a fire in your heart. Thank you so much for this interesting article!!!!

I, too, work in the ad industry (which I, too, dislike being a part of) and I cringe every time my daughter asks for more syrup – every single morning. She will only eat Aunt Jemima’s syrup and not the real stuff. Today I decided to look up the real facts of this syrup – which contains no actual maple at all. Then, I came across this article which helped solidify what we all already knew: that this product – like so many others – was not really designed for the betterment of society, but for a way to make money (argh!). I’m now totally refusing to buy this product ever again and if my daughter stops eating syrup altogether, then great! Thank you for sharing this extremely well-written piece.

Thanks for such a great post! Here’s one more chapter in the history of the Aunt Jemima advertising campaign used that I think you should know about.

During the 1930’s, Quaker Oatas would hire African American women to dress up as Aunt Jemima, get in character, put on the accent, and then go to supermarkets and country fairs to show Caucasian women how to use the pancake mix while performing in the role.

News journalist Michele Norris in her autobiography “The Grace of Silence” mentions how she discovered that her grandmother had at one time taken on this particular job in the Minnesota where Norris, her mother and grandmother were all raised. Give the book a read for more details.

the Pine-sol lady, the Popeye’s lady… what other women of color are there representing national brands, and in what capacity? I mean, it’s mildly disturbing.

Excerpted from A Lesson In Marketing Magic: The History Of Aunt Jemima | A Black Girl’s Guide To Weight Loss

The black actors and actresses in fast food commercials, most of the foods are processed and disgusting. It is very disturbing.

I have fond childhood memories of the old Aunt Jemima lady! I don’t think it has to be seen as all negative when people of color are being represented like this. It exposes the general public to different types of people and may open up their mind.

Nope.

The problem is the fact that this is the SOLE ways that black people – not people of color, black people – are represented, and it affects the way we are treated and respected in society.

Aunt Jemima isn’t the problem. The fact that her image was used, abused, manipulated, and perverted by racists and scumbags is.

It’s not wrong to have fond memories of the product. But we should be mindful of its sordid history and be sensitive to ways in which her image affects the way others are seen.

Have you ever saw the movie, “Imitation of Life” (the 1934 version)? It is eerily similar to Nancy Green/Aunt Jemima’s life, insofar as the black female star played an Aunt Jemima-type role, only she was named Aunt Delilah in the movie. Besides of the main point of the movie being about light v dark skin and passing for white, it also focuses on this black housekeeper, of a single parent white woman, and how Aunt Delilah and her went into the pancake business together, using the “mammie’s” recipe.

The business took off and became filthy rich. There were many disturbing scenes in this movie and a lot of negative black rhetoric. But the pivotal scene that sticks out is when the white business partner to the mammie tells her they are now rich, the mammie tells the white woman, “ize don’t want no money, me and Paola (her mixed daughter) just wanted to continue to live with them and continue to take care of them like how it started out with her being her servant. Incredible!

The timeline of that movie in 1934 and the timing of Quaker Oats buying the recipe is too close for comfort, for this movie and I always felt it was a joke on us that they were showing us who Aunt Jemima really was and her true story, but had our minds focused on the drama of the daughter who didn’t want to be black.

Many times, as we are learning, due to the internet information highway, as of late, that many enslaved black people created tons of the most used, necessary and money making inventions that are still used to date, so I do believe they stole her wealth, just like they did to countless others and take credit, while stealing black wealth.

The family also tried to sue them for that kind of money and calling it ‘repairations’ was a guaranteed loss. They don’t want us to start getting any ideas about reparations and no way in Uncle Sam’s hell, are they going to hand that bulk of money over to people of color. Thank you for this story and honoring the Queen.

Oh, also the 1954 version of the movie, Imitation of Life, left the entire pancake story line out of the movie. How appropriate. I guess they didn’t think people would pick up on the similarities of Art Imitating Life, and put 2 and 2 together.

Dear Erika and others,

The other day I was visiting my neighbor who is a white woman. I was wearing a scarf around my neck. When I playfull placed the scarf on my head, she looked at me and and calmly stated without reticence, “You look like Aunt Jemima.”

I was in shock and did not know how to respond. It is now two days after and I am feeling neither piece of mind nor peace in body and soul.

How would you suggest one handle a scenario like this? What would you have said in response?

Thank you,

Jo

Awww, wow.

Here’s my thing. Ask yourself what, specifically, upset you. Did it feel like a case of “they all look alike?” Did she, in equally playful demeanor, connect you to a timeless character? (Whether we like it or not, white folks may not always attach the same kind of baggage to Aunt Jemima like black folk.) Was she trying to use her name as a pejorative, and that upset you?

I’m a believer in creating, reinforcing, and defending boundaries. And, because this is a neighbor who you’re not likely to be able to avoid permanently, I’d have just said very plainly, “Aww, don’t do that.” When she replied, “What? You do.” like just about anyone would, then explain what it is that unsettled you. She can either apologize for being impolite or be a jerk about it, but either way, you know your role.

Since it happened days ago at this point, I’d let it go… but I’d file it away just in case you start collecting offenses.

Comments are closed.